Geographic inequality and learning in Peru: Evidence

from the reform period of 2007-16.

Contributors:

University of

Sussex, UK: Sonja Fagernas, Panu Pelkonen, Juan-Manuel del Pozo Segura, Diego

de la Fuente Stevens

U. Antonio

Ruiz de Montoya: Adriana Urrutia Pozzi-Escot (also Transparencia

Perú),

Funding: British

Academy

Date: May 2023

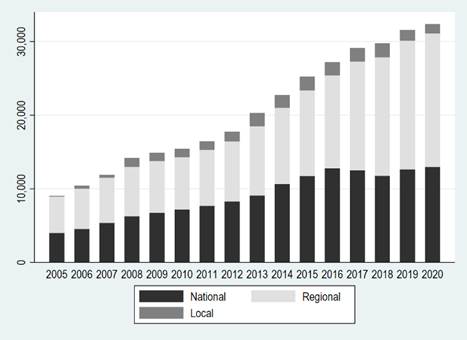

A set of significant educational reforms was

implemented in Peru during the decade of 2010. The education budget increased

substantially from around 2011 onwards (see Figure below). The period 2011-16

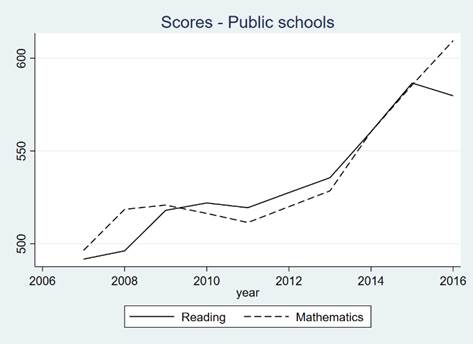

also coincided with a new government. The learning levels of primary schools pupils, measured as test performance, increased

significantly during this reform period.

Figure 1 Developments in the education budget Figure

2 2nd grade test scores in public schools

|

|

|

Our research project focuses on the changes in

geographic inequality in relation to primary schooling, during the reform

period of 2007-2016. We have sought to answer the following questions

1)

Did

inequality in learning between different regions/departementos

fall as a result of the reforms? How about inequality

between urban and rural areas? The answer turns out to be no, so we focus on

explaining the persistent urban advantage in learning, including factors beyond

the reforms.

2)

Did

the improvement in public sector learning levels allow public schools to catch up

with private schools? How did this affect the position of private schools in

urban Peru?

3)

How

was the regional education budget allocated over the reform period? To what

extent did it relate to the educational needs of the regions? Did observable

political factors affect how the educational budget was allocated across the

regions?

To answer these questions, we use data from a range of

sources, including school census data for all primary schools (Censo Escolar) and test score data for all 2nd

grade pupils (Evaluación Censal

de Estudiantes), data on the education budget from

the Ministerio de Economía

y Finanzas, the national household surveys (ENAHO)

and the national population census (Censo de

Población y Vivienda). Our findings are summarized

below.

1)

Rural-urban

inequality and learning [link to the study]

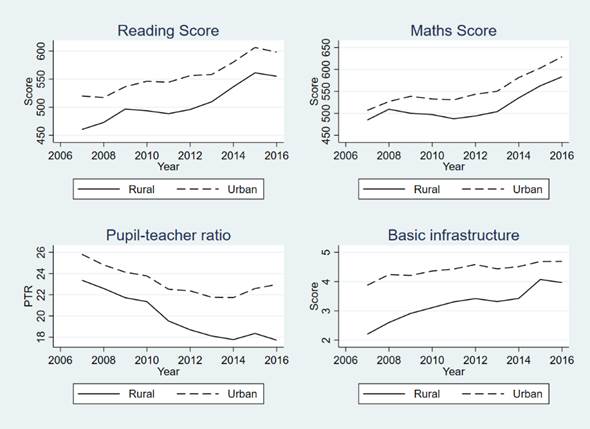

Several aspects of the educational reforms, and

especially the budget, favored remote or rural regions. Public sector schools

in rural areas experienced larger improvements in school inputs, such as

infrastructure and teachers. Despite this, learning in rural public schools did

not catch up with learning in urban schools on average. While Reading and

Mathematics test scores improved in rural areas, they also improved in urban

areas, in some cases even faster than in rural areas.

Figure 3 Key comparisons between urban and rural areas

Why did inequality in learning persist to this degree?

Our statistical analysis provides the following explanations for the public

sector urban learning premium. 1) Half of the urban learning premium can be

explained by differences in school resources. 2) The remainder can be

attributed to larger school size in urban areas, as well as factors beyond the

school system, such as household socioeconomic status. The reform period was

characterized by robust economic growth, which appears to have benefitted urban

areas somewhat more. Therefore, the reforms and educational investment can only

explain a part of the increases in learning.

From the perspective of an individual, learning could

also be improved also by moving from a rural to an urban area. A parallel

development to the educational reforms was rapid rural-urban migration in

several parts of the country. We show that rural-urban migration potentially

accounted for 20-30% of the improvement in learning in many regions. Moving

from a rural primary school to an urban secondary school is associated with a

small increase in learning, in both Reading and Mathematics.

Overall, the closing of learning gaps across areas can

be challenging, because educational policy cannot

influence all factors that affect learning, such as parental socioeconomic

status, wealth of an area, or even school size. To reduce regional or

rural-urban inequalities, educational policy should target school

infrastructure and multigrade teaching, although the latter can be a challenge

in rural areas.

2) Effect of the reform on private schools [link to the study]

Across the developing and

emerging economies, low-fee private schooling is advancing rapidly due to low

quality and capacity constraints in the public sector. The educational reforms

carried out in Peru provide a possibly rare example of how public investment in

education may reverse the balance between the public and private sector.

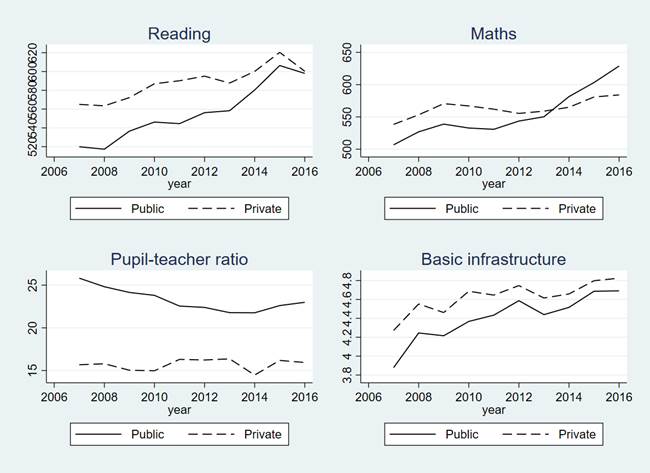

Figure 4 Key

comparisons between public and private urban schools

Our analysis here focuses on

urban areas and the period of 2007-2016. We show that as public

school test scores for 2nd grade pupils improved, the private

sector learning premium in urban primary schools largely vanished. While

private schools have been better resourced on average, learning levels in urban

public sector schools improved significantly from 2011 onwards and largely

caught up with private schools.

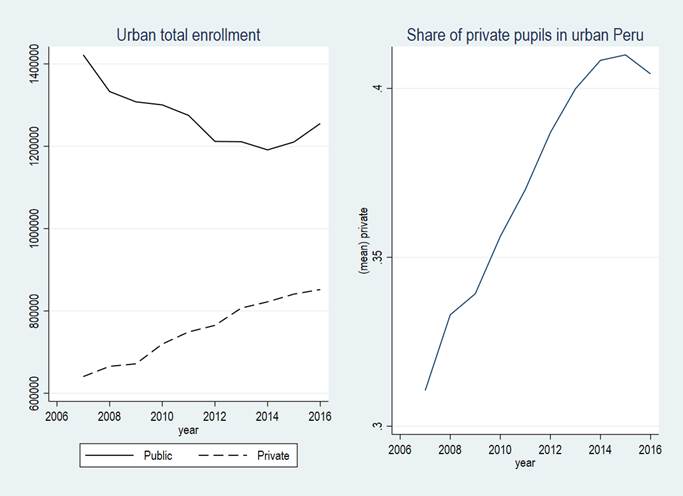

The growth of private primary

school enrolment in turn started to level around 2014, soon after the rapid

improvement in the public sector began (see figures below).

Figure 5 Private

and public primary enrolment in urban Peru

Given the average improvement

in the quality of public schools in the reform period, we can assume that

competitive pressure on private schools increased. We construct a measure of

competition faced by private schools from public schools, based on the number

of public schools within a specific radius for each private schools. The data

provides information of the location of each school. Our statistical analysis

reveals that post 2011, competitive pressure on private schools increased more

if there were more public schools nearby, the private schools were of lower

quality in terms of learning and parental income in the area was lower,

implying weaker purchasing power. In these cases, private schools were more

likely to close down and their enrolment declined more

in response to the improvement in public sector schooling in the post-2011

period.

The presence of low quality,

low-fee private schools is potentially a significant problem for the

development of skills in Peru. Our analysis is not a comprehensive study of

this sector, and regulation evidently has an important role to play. Our

results do suggest that significant investments in the public sector which

improve its quality, have the potential to slow the growth of the private

sector, and crowd out under-performing, private schools. A further analysis

would be warranted to study whether the impact is long-lasting. The key message

for policy would be to guarantee the existence of a good public sector school

within a safe and convenient walking distance for all families in urban and

peri-urban settings.

3) Allocation of the regional education budget: needs and politics [link

to the study]

We find that over the period, the allocation of

funding to regions became more “rational” in the sense that it more closely

tracks the expected funding needs. In the latter period, funding was directed

more towards regions that lagged behind in terms of

school infrastructure, and that employed more teachers per pupil population,

implying a larger wage bill.

However, there is also discretion in the allocation of

funds. As might be expected, transfers of tax income from natural resource

related activities (‘canon’ payment) are associated with higher regional

funding, beyond resource needs. Finally, our analysis suggests that political

lobbying may affect the discretionary component.

We find that if a

larger share of districts in a region has a member of congress, the region

receives more infrastructure funding, and has a larger number of new schools.

Members of congress tend to come from larger cities

and this tends to concentrate them to fewer districts. However, if a region has

a number of successful candidates from more rural

locations or smaller towns, the share of districts with a member of congress

can increase. This in turn can influence budget negotiations.

Overall, we do not

find that regions that obtained more funding than expected, managed to translate

this funding into larger improvements in learning. Rather, learning outcomes

improved across regions, irrespective of some discrepancies in funding.